I'm always excited to take on new projects and collaborate with innovative minds.

No 7 High tension road Aroma junction Awka Anambra state.

I'm always excited to take on new projects and collaborate with innovative minds.

No 7 High tension road Aroma junction Awka Anambra state.

A detailed walkthrough on my approach to usability testing, from planning and recruiting participants to turning feedback into real, impactful design changes.

Not every usability study actually improves a design.

Sometimes it’s a checkbox activity run a few tests, gather some quotes, slap “usability tested” in your case study, and move on.

I’ve been guilty of that early in my career. But I learned that a usability study is only valuable if it changes something.

These days, I run usability studies with one goal in mind: find out exactly what’s stopping the user from loving this product… and fix it.

The worst usability studies are the ones where you already think you know the answer.

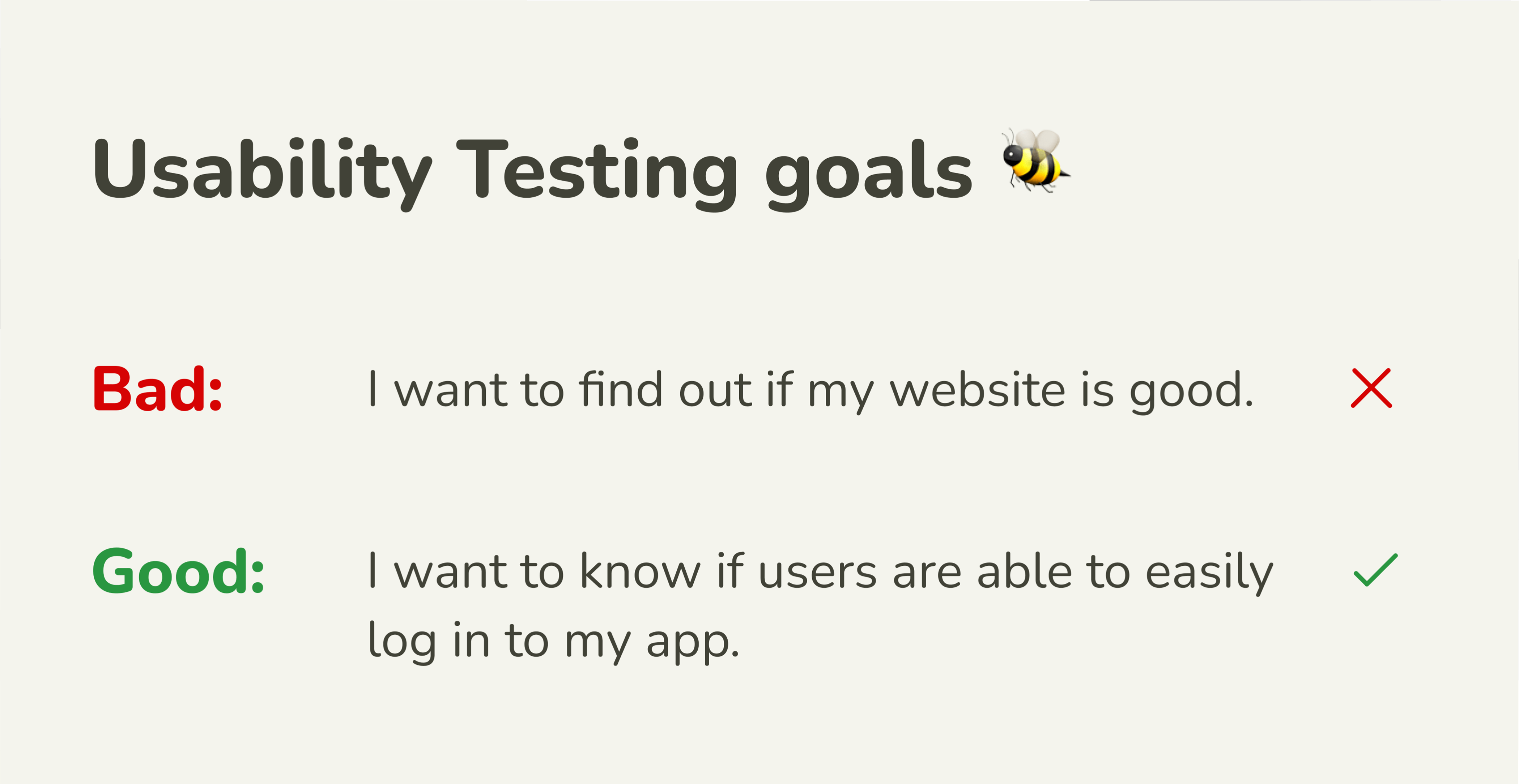

Before I run a study, I ask myself:

If you can’t answer those questions, you’re not ready to test yet.

It’s tempting to test with whoever is around friends, colleagues, your cousin who “likes tech.”

But I’ve learned that if you want insights that matter, you have to test with people who actually match your target audience.

For example, when I tested my NoWahala gas refill app, I didn’t just grab random testers. I found:

They were the ones who felt the real pain I was designing for.

A usability test isn’t about watching someone tap buttons in a vacuum. It’s about watching them try to accomplish something they would actually do in real life.

If I’m testing a trading app, I’ll ask: “You want to buy ₦5,000 worth of Bitcoin, show me how you’d do it.”

If I’m testing a food app, I’ll ask: “You’ve got only 20 minutes to make dinner, find a recipe and start cooking.”

The more realistic the task, the more honest the feedback.

This was the hardest part for me to learn. I used to over-explain during tests guiding users, answering questions, nudging them toward “the right” path.

Now I give them the task and let them wrestle with it. If they get stuck, that’s not failure: that’s the insight I came for.

One person struggling might be a fluke.

Five people struggling at the exact same point? That’s a design problem.

I organize my findings into three categories:

This keeps me from overreacting to one-off comments.

Here’s where many usability studies fall apart: the findings get documented… and then forgotten.

I make changes fast, even small ones so I can test again while the context is fresh.

Sometimes it’s as simple as renaming a button, adjusting a layout, or adding a confirmation step.

The point is, research is useless if it doesn’t lead to design action.

A usability study isn’t about proving your design is perfect it’s about finding out where it isn’t, and having the humility to fix it.

I’ve stopped thinking of testing as the final step before launch. Instead, it’s an ongoing conversation with the people I’m designing for. And honestly? That’s when design gets really good.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *